Week 13: Going West

–

–

We tried to take care of a few things before leaving Beijing but were relatively unsuccessful. One pretty important thing we looked into was extending my Chinese visa to allow me to stay in China while Brett goes back to work. The longest visa I could get in Seoul was 30 days and while it’s possible to extend that for up to 60 extra days I need to open a Bank of China account and deposit US$100 per day that I want an extension. So for a 30 day extension I need to deposit US$3,000. I assume this is to prove that I have “sufficient funds” though most countries would be happy with a print out of my Australian bank statement (which I think is completely reasonable). Personally I remember opening a Bank of China account to be a process taking many hours and resulting in much frustrated pulling of hair. It’s not a process I want to go through again and it’s not a process I’d wish on any unsuspecting tourist who happens to want to spend more than 30 days exploring this massive and varied country.

Thankfully for me China’s ridiculous rules go hand in hand with rampant corruption, and for a certain extra “fee” there is a company that will “take care” of my extension without me opening a bank account. It will cost me 860 yuan (about US$125) for a 1 month extension and I’ll need to do this twice. China has just priced itself out of the backpacker market, but maybe they want to? Backpackers stay too long, talk to people and want to understand the country; maybe they’d prefer high end, short stay group tourists who only see smiles? It’s hard to tell what they’re aiming to achieve sometimes. Maybe they don’t understand that making people feel unwelcome will drive them away?

I’mgoing to spend the time Brett’s away working on my Mandarin in Beijing, though sometimes it’s hard to see the point of further study (see above). It’ll be nice to be based in one place for a while though, hang out with some friends I have there and hopefully do some photography. I’ll also be sorting out visas for Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and maybe Kazakhstan for Brett’s next break. We’ll be heading to Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan for 6 weeks then I’ll hang out, maybe in Almaty or come back to China (if they’ll have me). The break after that we’ll go to Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. Then maybe Iran, the Middle East and Egypt. Who knows where after that?

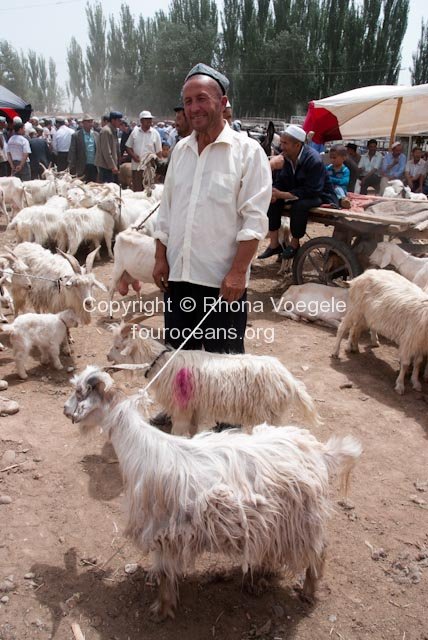

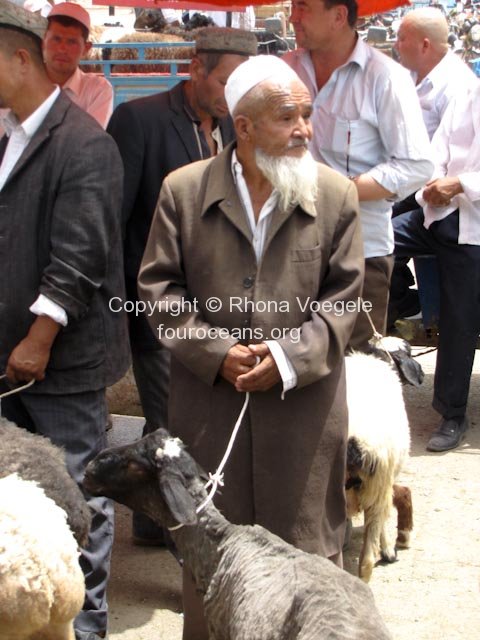

At the moment we’re in Turpan, Xinjiang province. It’s like a different country here, the people, the language and the food is all completely different to China. Depending on who you talk to Xinjiang should be an independent country, though the Muslim Uyghur minority group don’t seem to get the same sympathetic support as Tibetans from the international community. Personally I think they rock, they’re such a breath of fresh air. The smiles are genuine and I’m always treated well here.

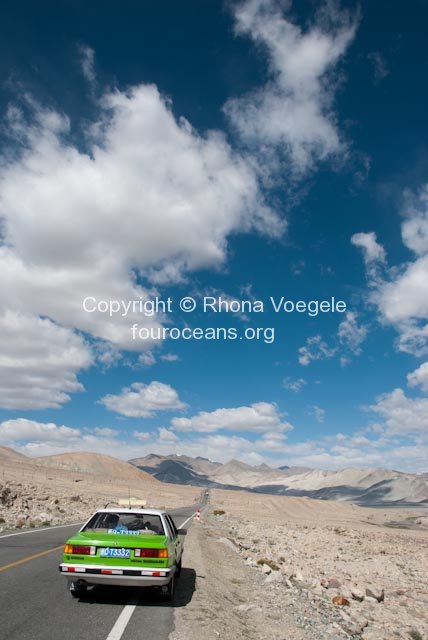

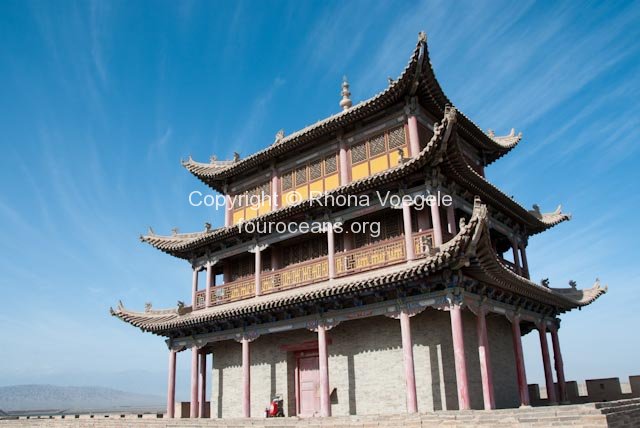

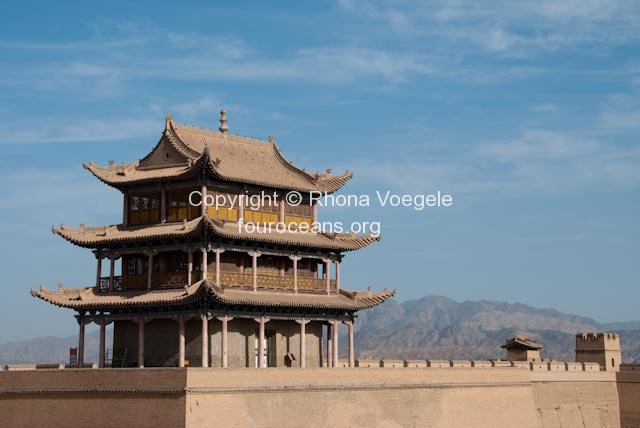

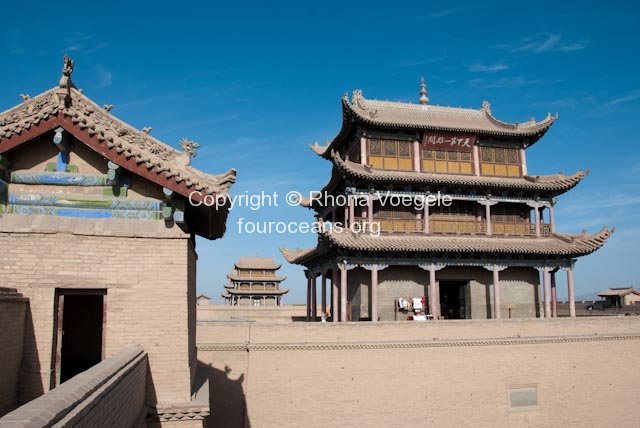

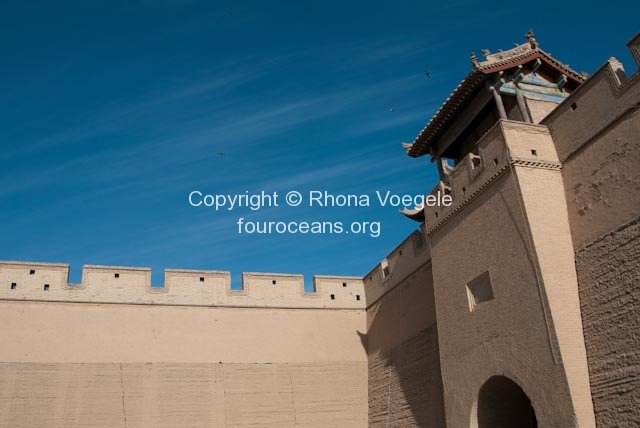

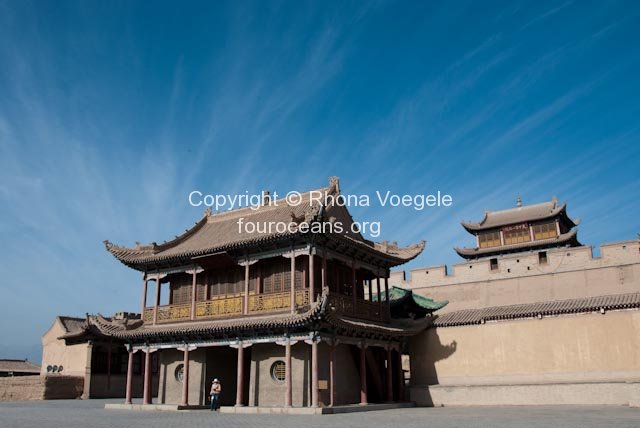

We stopped at a few places on our way west, first at Jiayuguan in Gansu province, the Western end of the Great Wall and China’s last major stronghold on the road west. One is asked to politely overlook the fact that Xinjiang is west of here. It’s in the Hexi corridor, a narrow strip of flat land between the Mazong, Longshou and Heli mountains in the north and the Qilian mountains in the South. All overland trading caravans heading west from China came through here and during the peak of the Silk Road jade, silk, porcelain, spices and horses made their way around the Taklamakan desert to reach as far as India, Persia and the Mediterranean.

A little further west was Dunhuang and the nearby Mogao Caves. There are 735 caves in total, 492 of which are painted with Buddhist art from a massive variety of eras. The first cave is said to have been painted in 336AD and the site was active until the 19th century. A little further west of Mogao the Silk Road split into the northern and southern routes around the Taklamakan desert. Travellers stopped at Mogao to pray for a safe journey or give thanks for a journey safely completed. Our guide took us in to a small selection of caves and told us some of the history. The artwork was incredible, the detail and the line work in the figures are breathtaking and even an ignoramus like myself can see differences in the styles of different eras. In some of the earlier caves the figures are more slender and almost feminine while later ones are more solid and masculine. Many of the caves were built on behalf of wealthy patrons and there are often images of the sponsors as well as details about them painted on the walls. Of course we were taken to the library cave where various foreign devils made off with about 40,000 priceless manuscripts, paintings and scrolls that were discovered sealed in a secret room. There were another 12,000 items left behind, the best of which were divided up amongst various Chinese officials and are lost to unknown private collections. The foreign devils donated their findings to museums and public institutions where most of them remain, albeit not in the country they were discovered in.

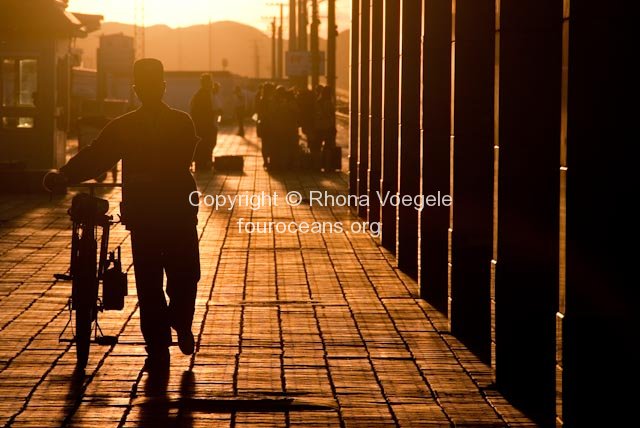

The day before yesterday we arrived in Turpan, our first stop in Xinjiang. We spent the day hanging out, exploring the bazaar and sheltering from the heat of the day in our hotel room (it was about 36 degrees celcius and baking hot in the sun). At the market we discovered tangzaza, triangles of sticky rice that are squashed a little and covered with syrup. Totally delicious. We also tried samsas, baked dumplings filled with mutton and maroji, ice cream with a rich vanilla flavour and a hint of an unidentifiable spice. Back out in the cool of the evening we bought ourselves a watermelon from a small stand, cut it in half and asked the shopkeeper for 2 spoons.

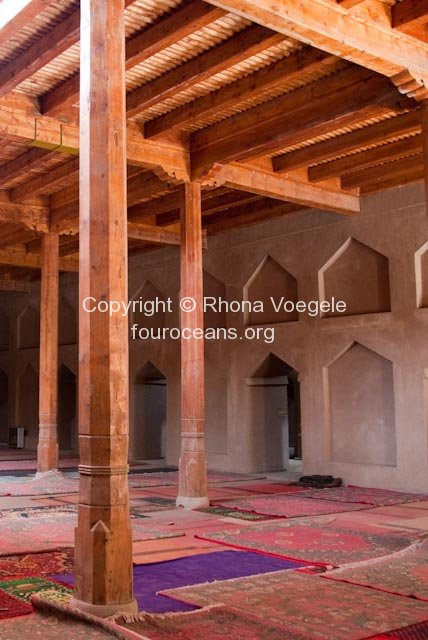

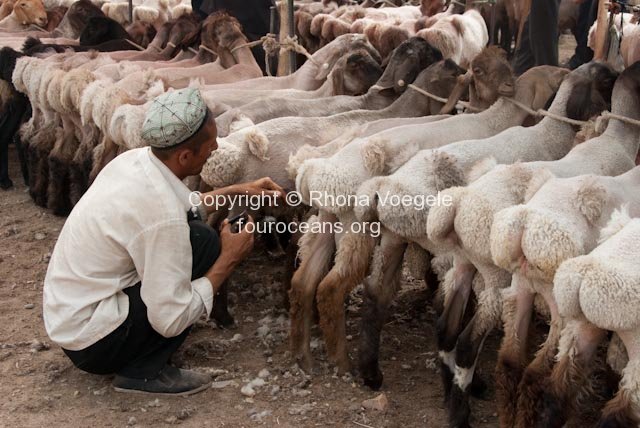

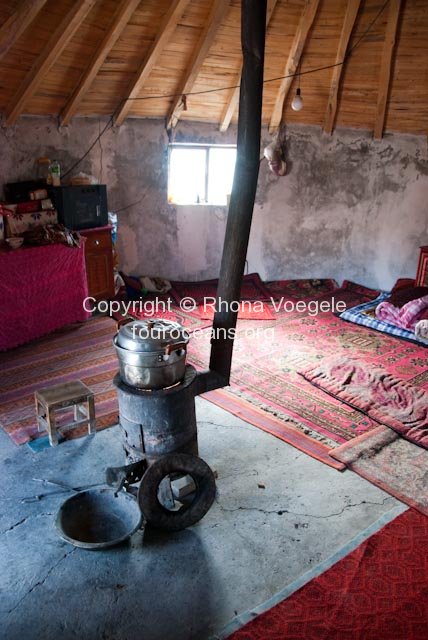

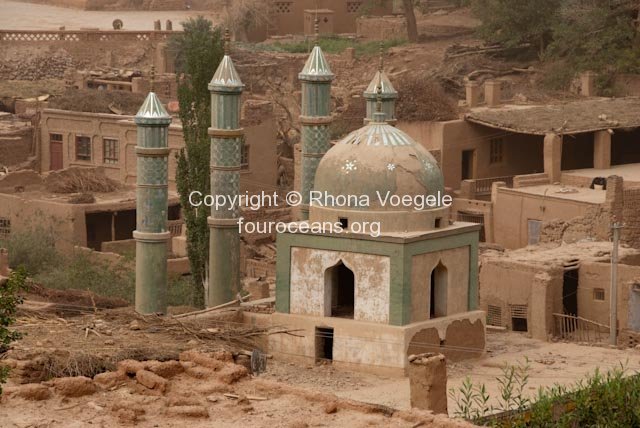

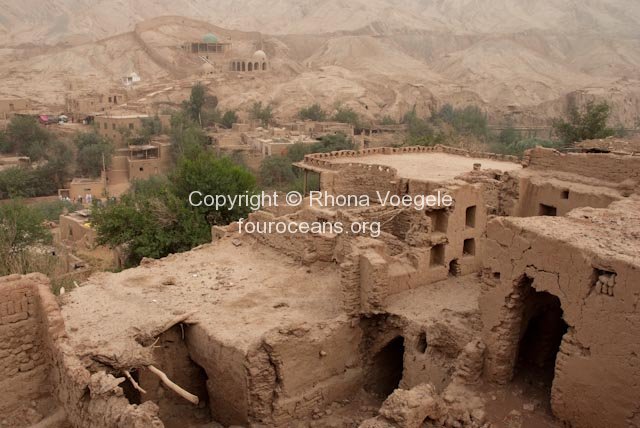

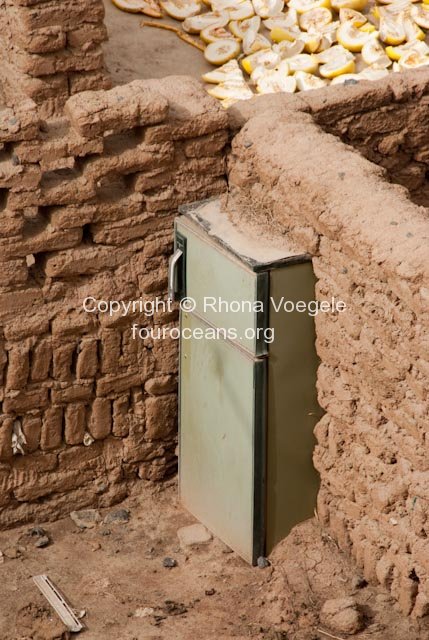

We went to bed at 10pm Xinjiang time and were up at 6:30am Beijing time. Beijing time is 2 hours ahead of (unofficial) Xinjiang time because Beijing prefers to ignore the fact that Xinjiang is so far west that it needs a different time zone. We’d organised a car to drive us around the sites near Turpan and spent the morning at Tuyoq and Bezeklik caves. Tuyoq is a small Uyghur village which is near an important pilgrimage site for Muslims in Xinjiang. The Chinese government makes it close to impossible for Uyghurs to get passports and so they’re not able to fulfil their obligation to make the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. According to our guide the pilgrimage to the symbolic tomb of the first Uyghur Muslim, on the hillside nearby, is regarded as close enough. We met a man who had come from Kashgar on pilgrimage with his family and bought 3 goats to be sacrificed. The internal organs and head of one of them lay around on the dusty ground as another one was skinned. A goat costs 500 yuan, about US$75, quite a price for a local. As far as we could tell the villagers sell the goat to the pilgrim, it is sacrificed and then the pilgrim distributes the meat amongst the villagers. Not a bad deal for the villagers really.

Bezeklik caves are largely empty. The walls were once covered with Buddhist murals but most has been lost to pesky foreign devils, vandalism or the general wear and tear of time. Again, to be fair to the foreign men who quite literally cut out many of the frescos and left gaping holes in the walls, the ones that remained had their faces gouged out, their golden halos scraped off and were covered with wads of mud thrown where vandalising hands couldn’t reach. Unfortunately for many of the stolen frescos they were taken by a German, Albert Von le Cog, and were lost in the bombing of his country in WW2. Pass the blame to the Allies I suppose.

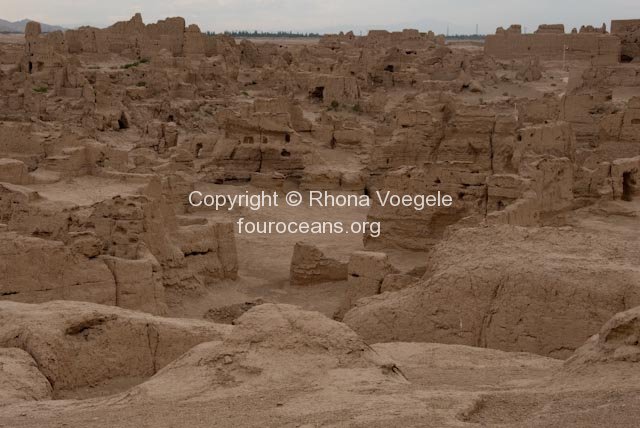

In the afternoon we visited the ancient city of Jiaohe, on an island between two rivers. Settled in 108BC and lived in until the end of the 14th century, many buildings are still recognisable and the main monastery still has partial statues of Buddha visible. We wandered around the streets and then headed back to our driver who took us to see the karez irrigation system. Water is channelled from the mountain snow melt into channels that run underground to villages. Oases like Turpan rely on these channels for their water and the underground tunnels are cleaned out once a year by men who drop down into the holes that are spaced every 5-10m along the channel. Grapes are an important crop in Turpan and our driver took us to his family’s grape plantation. Harvest is in about a month so the grapes were still a little sour but I’d love to be here in grape season. We might be able to buy some early harvest grapes before we leave Xinjiang.

Today we catch the train to Kasghar to get there for the Sunday market, then we head down to Hotan and across the Taklamakan desert to Urumqi. From there it’s back to Beijing in time for Brett to fly out to work.