–

–

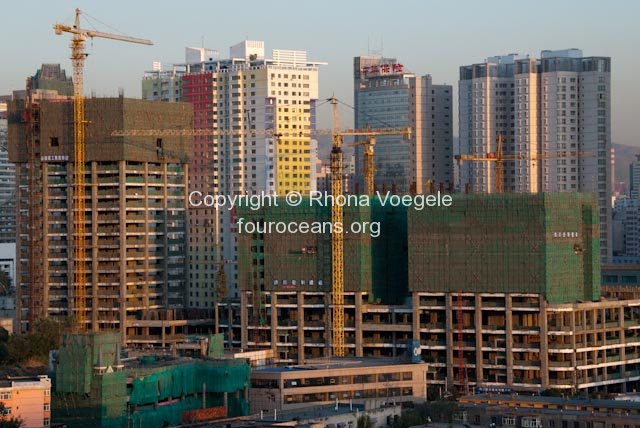

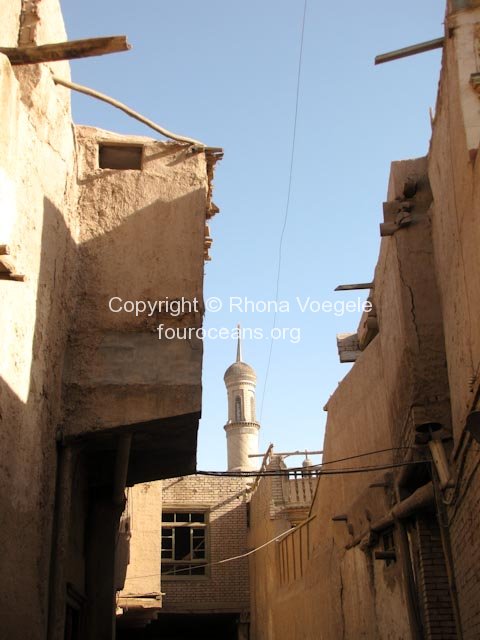

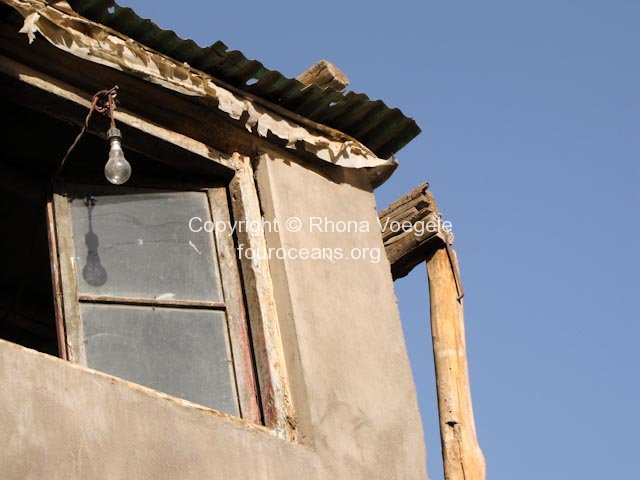

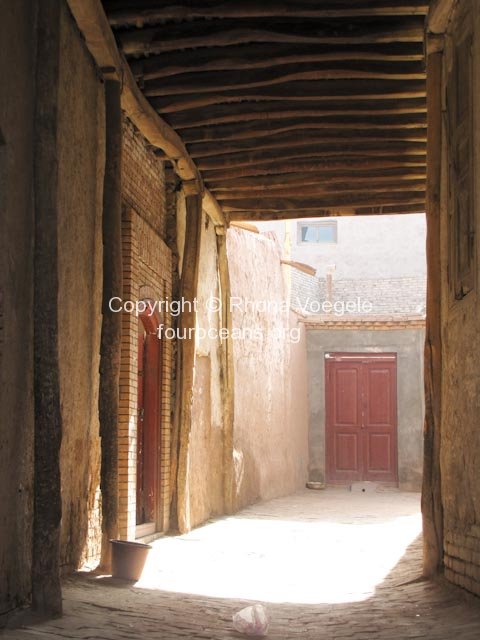

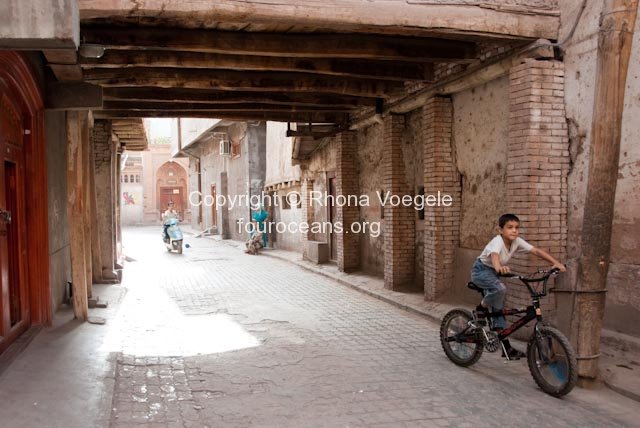

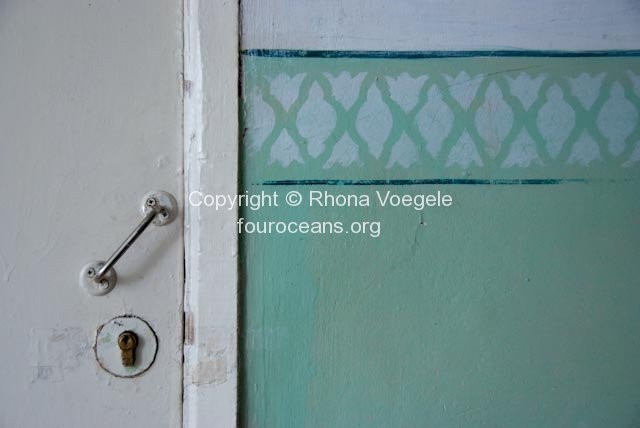

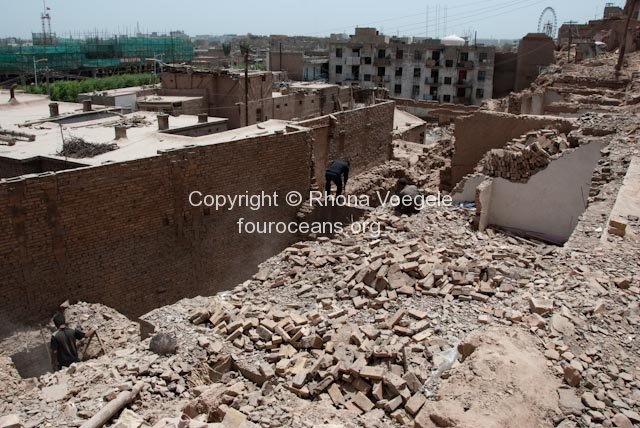

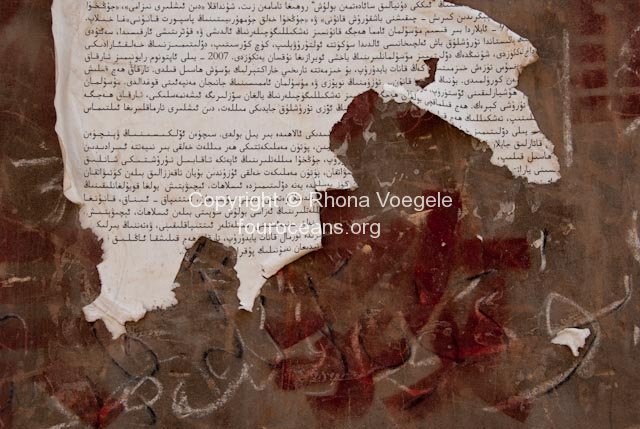

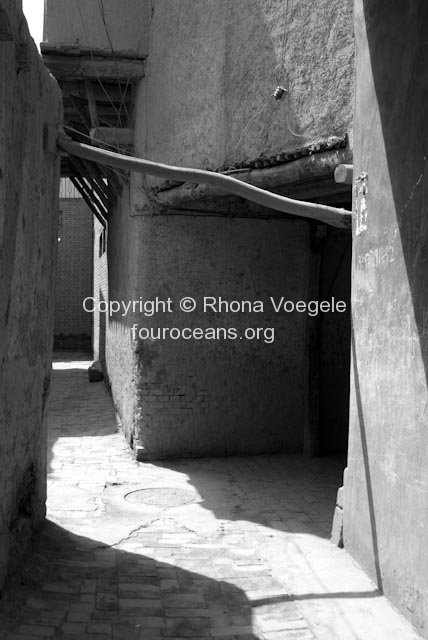

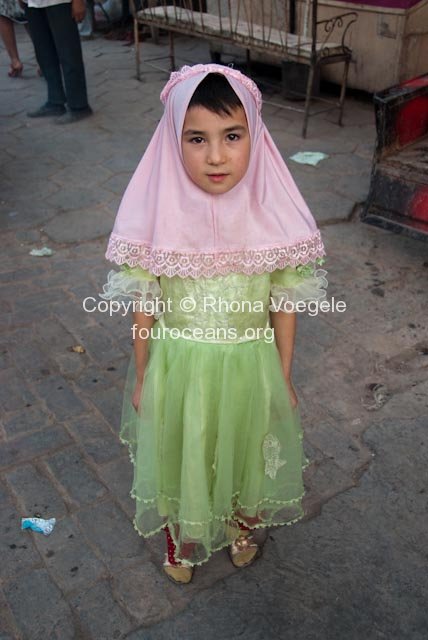

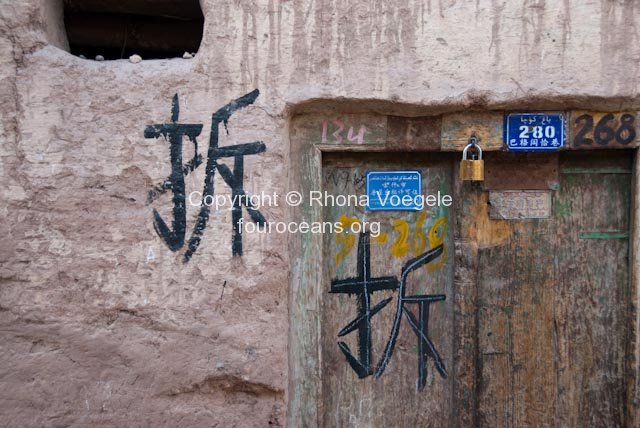

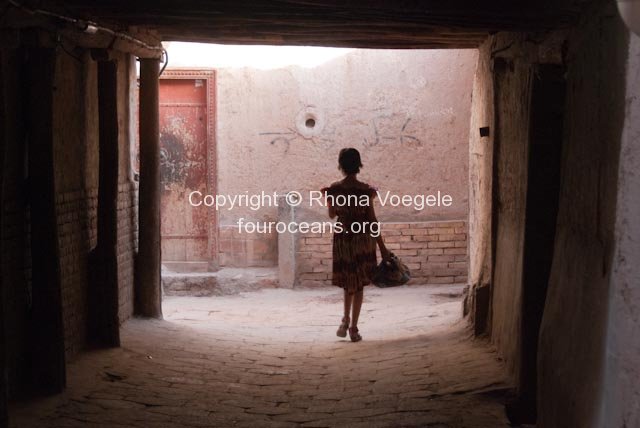

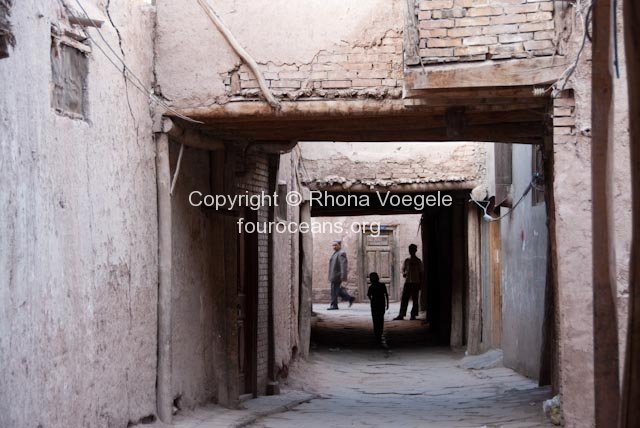

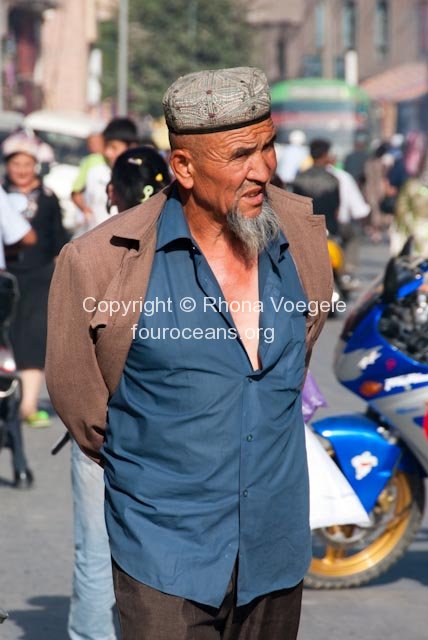

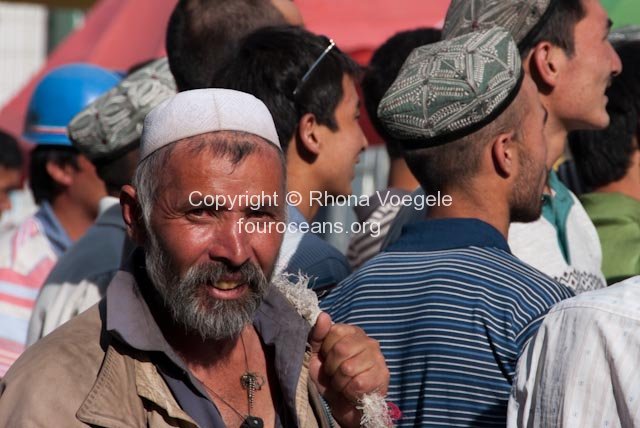

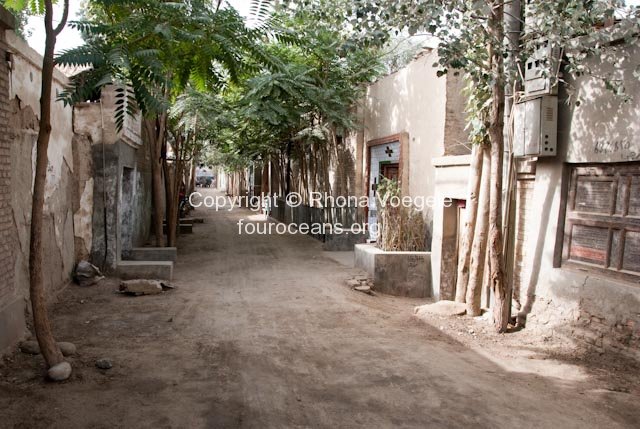

It was hard to tear ourselves away from Kashgar, particularly our hotel room. We don’t often get attached to hotel rooms but this was a heart stealer – the perfect travel room. The location, staff, bed and shower were all perfect and it was also the cheapest room we’d had so far. But quite apart from that little sweetener Kashgar is quite simply an amazing place. We spent the last few days wandering around what remains of the old town. The heart of the city is a rabbit warren of tightly packed courtyard houses where the Uyghur people have lived for generations. It’s also prime real estate. As we walked around it was easy to see that old town’s days were numbered – the houses are being torn down by the government to make way for the sort of generic city centre that they prefer. Uyghur residents are being moved to the outskirts where land is less valuable and as usual in China they’re not happy with the compensation. But what can they do? As one told us, “There are no laws in China”. We walked through large swathes of the old town that have been reduced to rubble and dust, small pieces of beautifully decorated walls peeking out through the destruction, reminders that someone’s house once stood here. Not far away green cladding covered a construction site.

At one stage we walked out to a main road and realised we were in what had once been the paid section of the old town, an area cordoned off where the local government charged a 30 kuai entry fee. There was nobody collecting tickets because there was nothing left to see. The ticket sellers have been moved to another area where an English guide tried to get us in by assuring us that this neighbourhood would be knocked down in a year or two so we’d better come in and see it now. We declined but a busload of Han Chinese tourists enthusiastically followed their pretty female tour guide into the pay per view city. It’s hard to comprehend or explain the destruction that is going on in China. The hutongs in Beijing, the old town of Kashgar, and I’m sure many other historic places around the country are being completely destroyed and there’s no point in protesting because it’s the government, in cahoots with developers, who are swinging the wrecking ball. Attitudes toward preservation are starting to change but not quickly enough to save these places.

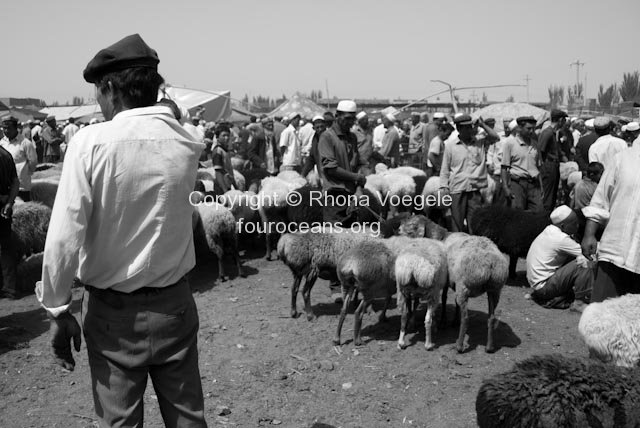

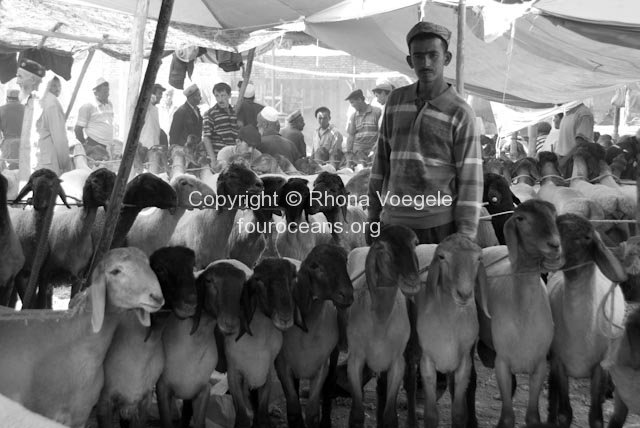

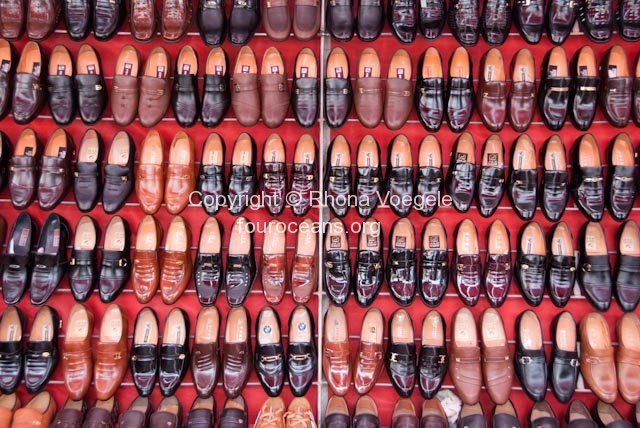

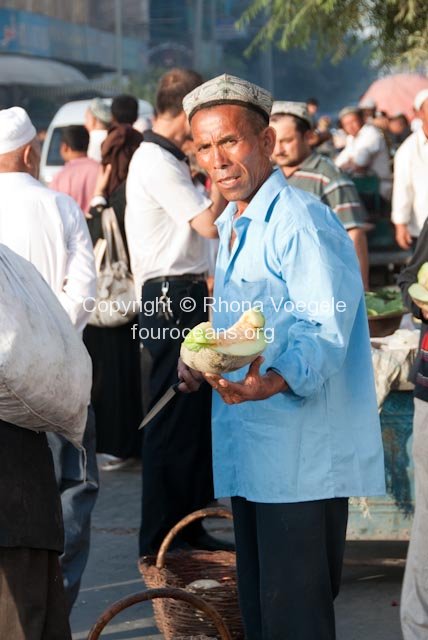

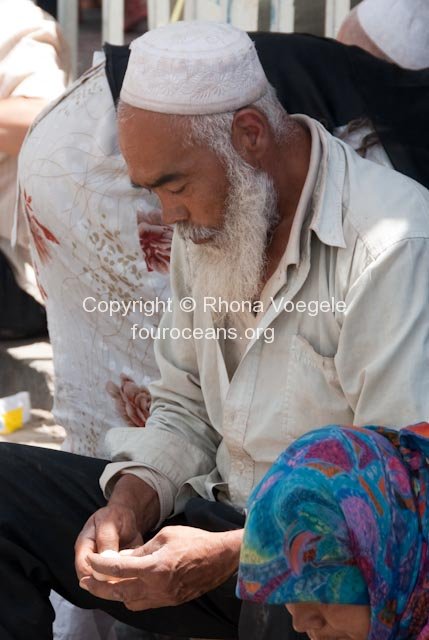

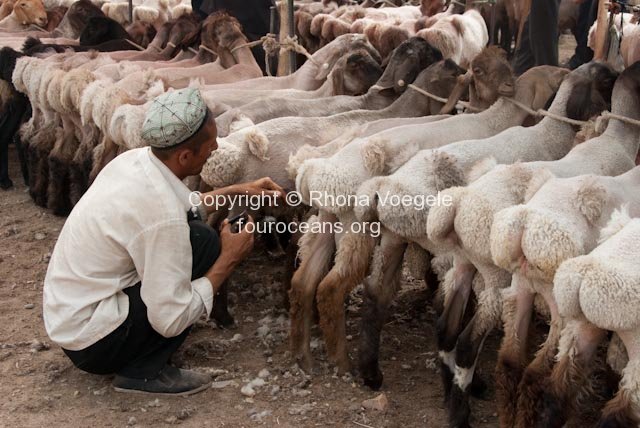

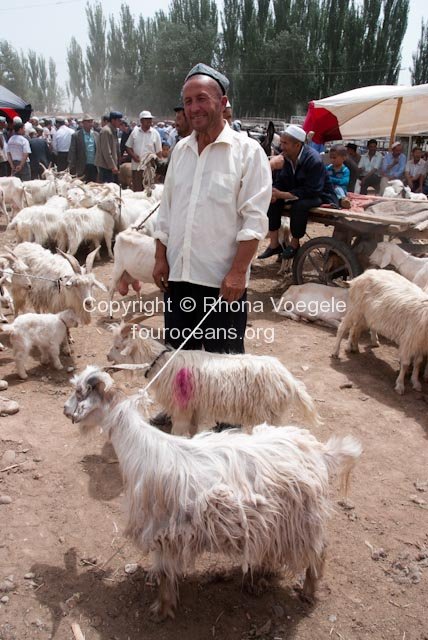

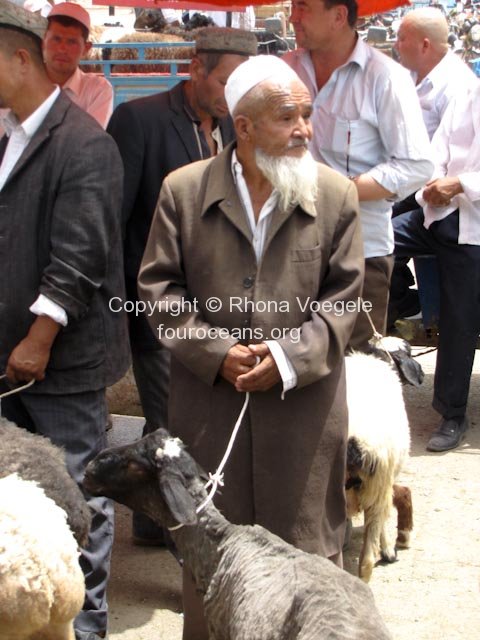

On a cheerier note the bus ride to Hotan was horrible and first impressions weren’t great either. Maybe it was the brothels only thinly disguised as hotels that lined the street coming out of the bus station? The kind of place that every bed comes with an accommodating woman. I’ve been there twice before but struggled to find the city I remember. The Sunday market was great though and apparently it’s the biggest in Xinjiang. I thought that was Kashgar but I guess I got that wrong. Hotan’s jade has been traded since 5,000BC and there was still plenty of it left to sell – big sheep-sized chunks of it down to small pebbles polished and coated with oil.

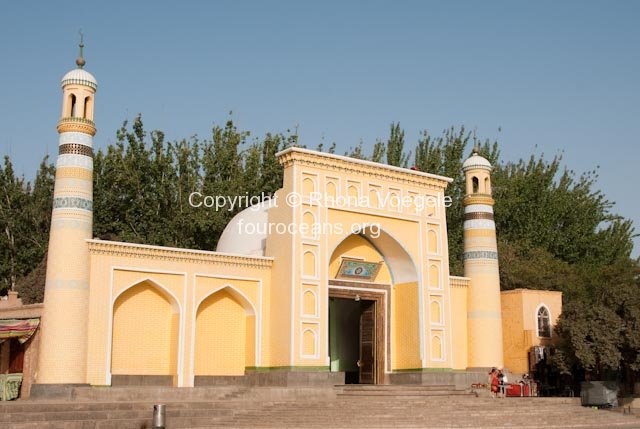

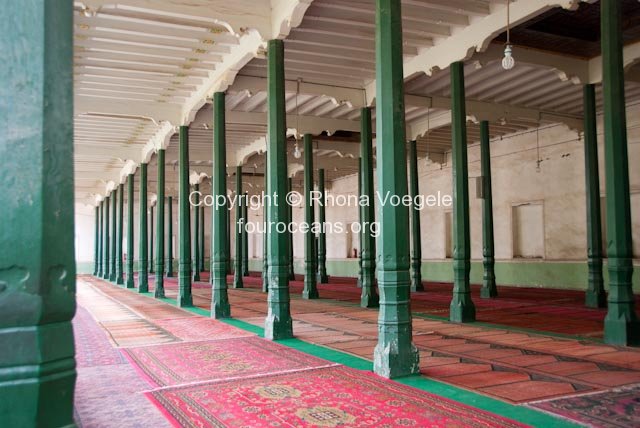

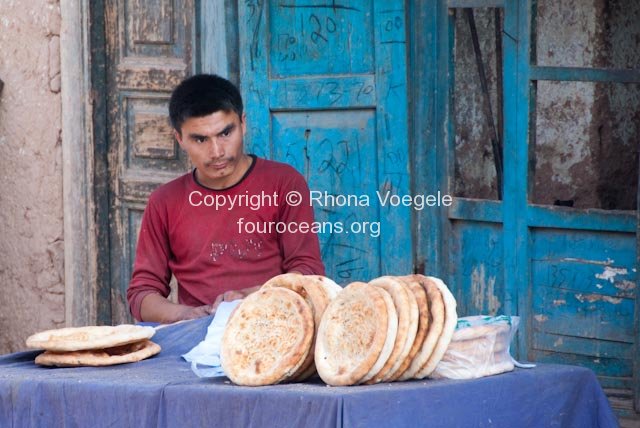

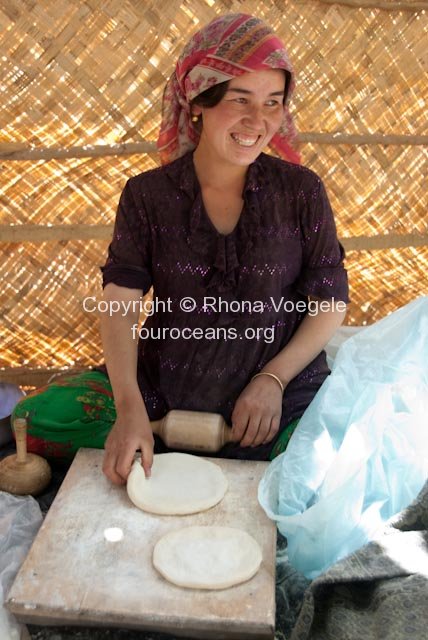

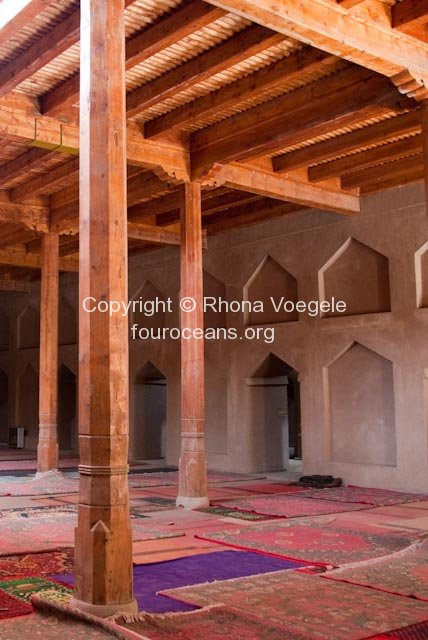

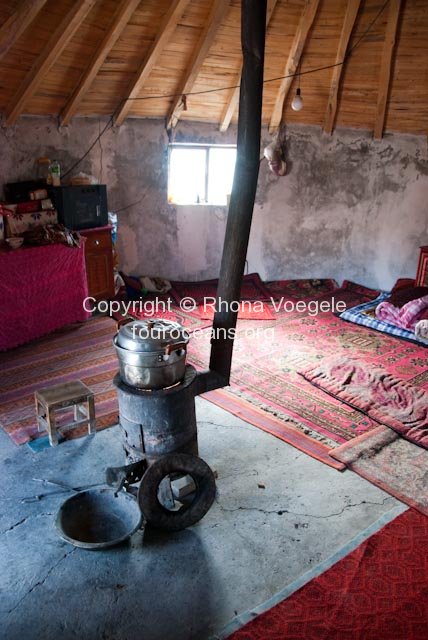

Outside town we went to a place called Imam Asim which is the tomb of one of the first men to spread Islam in this area in the 11th century. The tomb was on the edge of the Taklamakan desert and we wandered for a while in the dunes before heading back toward civilisation in search of a drink. In no hurry to head back to Hotan we dallied in the villages along the road home, ate some freshly baked naan bread, visited a silk factory and had multiple cold drinks.

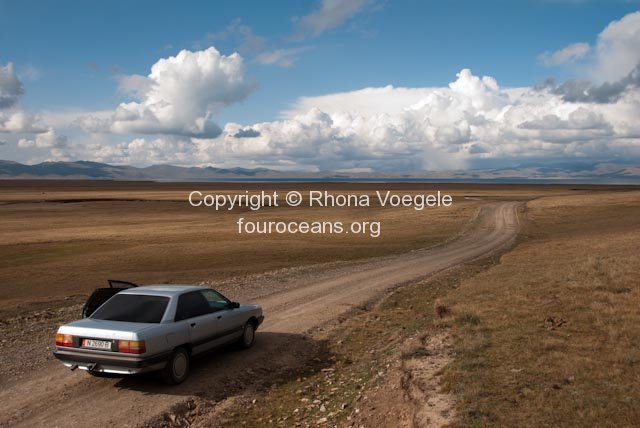

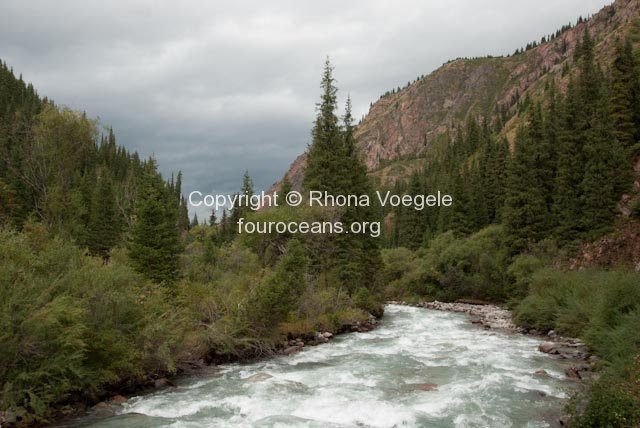

The next day we caught a bus across the Taklamakan desert to Aksu. The road we drove along had been open less than 2 years and is the second across the desert. Dune stabilisation is important to keep the shifting sand dunes from covering the road and about 3m on each side is covered in squares of reeds. Further out a fence of reeds stops sand from approaching the road but I wonder how easy it will be to stop the movement of the sands in the long term? I guess the first road across the desert, built in 1995 is still OK so they must know what they’re doing.

En route to Aksu a text message from my dad told us that something was going on in Urumq1. We were planning on arriving there the next morning but decided to avoid it after hearing details from him and also talking to someone we were planning on visiting in the city. At the time we thought it was a protest by Uyghurs and a brutal response by the army but the truth (when we finally found out) is that and so much more. We couldn’t book train tickets all the way to Beijing so we bought to Lanzhou (38 hours) and decided to look up options from there to Beijing online. Beware: saga following.

There was no internet connection in all of Xinjiang. We had to text a friend in Beijing to get the phone number of a travel agency because the local agency couldn’t book anything. Their entire system was based on having access to internet and so they could do nothing. We called and booked a plane ticket from Lanzhou to Beijing but couldn’t pay for it as we had to register our card details online. Back to trusty Robin (bless his heart) who went through the process for us from Beijing. The credit card was denied so we had to call the U.S. based bank but we were barred from making international calls (another part of the communication lock down). Thankfully at that time text messages still worked (later both domestic and international text services were blocked) and so we managed to get in touch with Brett’s family in the states. They could unblock the card but they needed to talk to Brett himself. Their department wasn’t allowed to make international calls and we couldn’t call them. Stalemate until Brett’s dad called someone in the bank that knows him and Brett. Small town connections came through and finally at 2:30am we managed to confirm our flight.

The next day we went to try to extend my visa and the amount of security was incredible. As we were waiting for the PSB (Public Security Bureau) to open a convoy of trucks full of soldiers in riot gear parked outside. Surveillance vans bristling with communications technology and small round windows for video cameras cruised the streets. Inside I was told that I had too much time left on my visa even though in Hotan they could have extended it the day before if we’d been there. We mentioned that we’d been planning on going to Urumq1 but now simply wanted to leave Xinjiang and in an exchange that I still can’t quite believe happened the officer told us that Urumq1 was now safe and that there was nothing abnormal about Aksu at the time. I could use (and have used) all manner of expletives to describe this irresponsible (adjectives deleted) man who would toe the party line ahead of looking after the safety of two bumbling tourists. Urumq1 is a chaos of vigi1ante attacks and people are being murd3red by mobs based purely on their ethnicity. The army is sho0ting into crowds. The train station where we would have come in is listed as a hotspot. The chances of being caught in the crossfire of racial hatred are extremely high, to say the least. And yet on July 7th Mr Chen (badge number 140486) assured us that it was safe to go there.

He also told us that the 40 s0ldiers in full riot gear with machine guns encamped in the PSB a few metres from where we were talking were simply “relaxing”. A prisoner shuffled past with hands cuffed to his shackled feet. Walking as he did, completely bent over, it was impossible to tell if he was Han or Uyghur. Something is rotten in the state of Denmark.

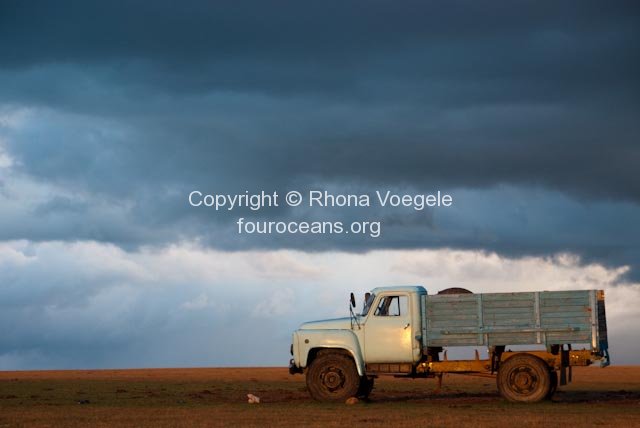

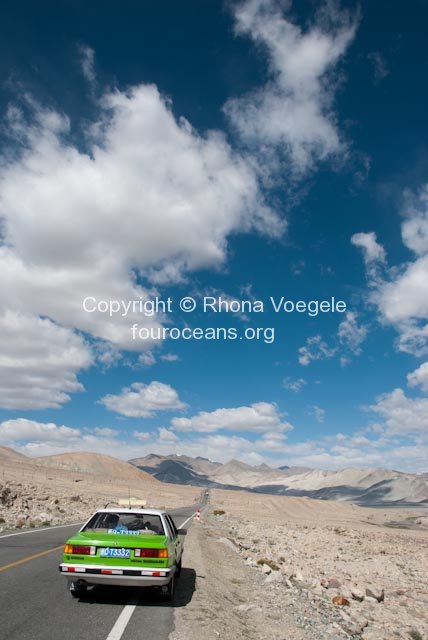

Our 38 hour train took us into the province neighbouring Xinjiang. It’s easy to forget how big and far away Xinjiang is from the rest of China. From Beijing to Kashgar takes about 75 hours on the train and we weren’t really far from Kashgar. Our flight from Lanzhou to Beijing accrued more frequent flier miles than the one from Seoul to Beijing. Security on the train was tight, my bag was opened going in to the train station for the first time in years of travel in China and before we left Xinjiang a policeman came through and scanned people’s ID cards in a device that obviously had a list of people who should not be allowed to flee. As soon as we left Xinjiang we could send text messages and make international calls. In Lanzhou we went on the internet and found out for the first time the true extent of the chaos gripping Urumq1. Convoys of army trucks headed west as the trains of oil headed east.

Back in Beijing it’s easy to be optimistic about China’s ability to change but at the same time the divide between the coastal and interior areas is growing. Even within the city there are migrant workers barely eking out a living as Ferraris drive past. It’s easy to be cynical about people with a lot of money in China but I think the best thing that can happen is for a growing middle class to realise that their own country needs to change. It’s hard as an outsider not to come across as anti-Chinese when I get frustrated with China and I hope that the Chinese themselves can make it a better place.

Talking about Xinjiang it’s very easy to make it into a black and white picture but that’s not how it is. Hatred and tensions have been simmering for decades, exacerbated by pro Han policies promoted by a government terrified of Uyghur autonomy which they fear may lead to Xinjiang breaking away. The individuals being murdered by vigilantes in Urumq1 (Han and Uyghur) are no more to blame for the situation than I am for say the White Australia policy (as an Australian) or the Nazi Gas chambers (as a German). Having said that both of those are in the past and I hope that Han Chinese today take a good look at their government, themselves and what’s happening and find a way to make things better. I can’t do it; I’m just a little outspoken laowai who tells it like I see it.