–

–

From Beijing the train to Urumqi took 40 hours but the time passed relatively quickly thanks to a book and some entertaining compartment mates. In Urumqi I was met at the station by my couchsurfing host for my first couchsurfing experience. We went to lunch then headed to the police station to register me as staying at his house for the night. When the riots happened at the start of July he hadn’t registered two foreigners staying with him because he didn’t know it was required. As a result he was demoted at work and doesn’t know if he’ll ever be allowed back to his original position. He’s Uyghur.

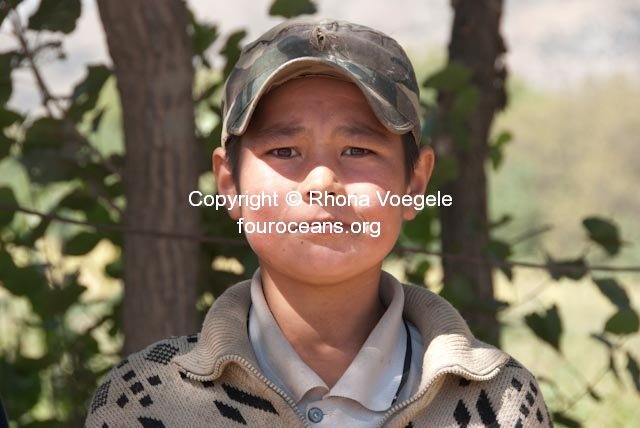

While I was in Urumqi he took great care of me and when he had to go to work the next day some of his friends took me around town and to the museum. On display are some incredibly well preserved (European looking) mummies from as far back as 1800BC! All the sections had English, Uyghur and Chinese captions except the modern history section which was lacking English explanations. Presumably because foreigners would ask awkward questions like “If Xinjiang has always been an inalienable part of the glorious motherland then why did the Red Army need to march in here with a buttload of tanks and German made machine guns in 1949?” or “was the plane crash that killed all the important leaders of East Turkestan as an independent country really an accident?”. And yes, much as I joke about it, “Xinjiang”, “inalienable” and “motherland” were indeed used in the same sentence.

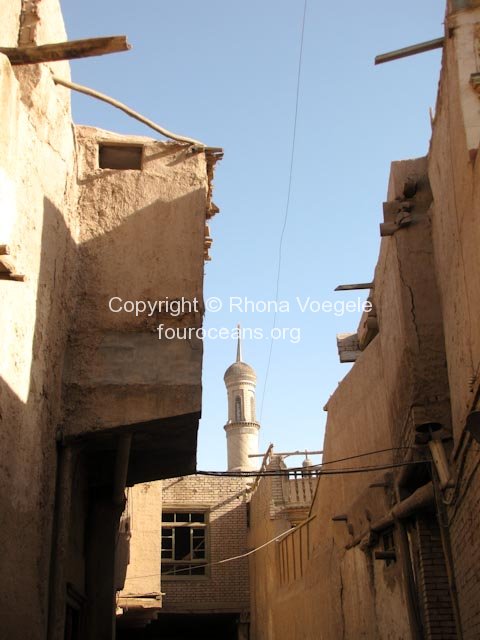

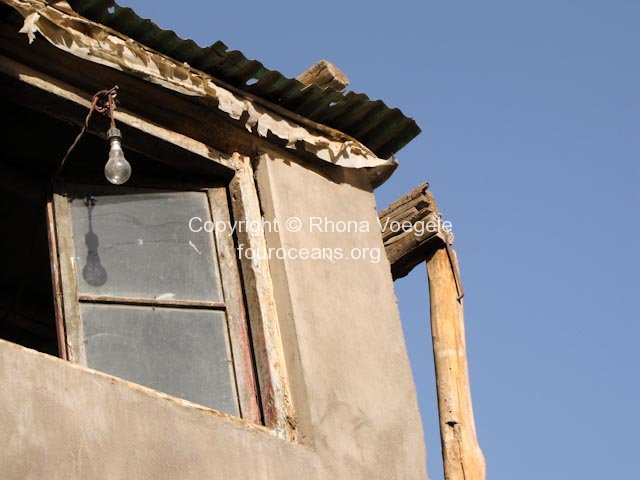

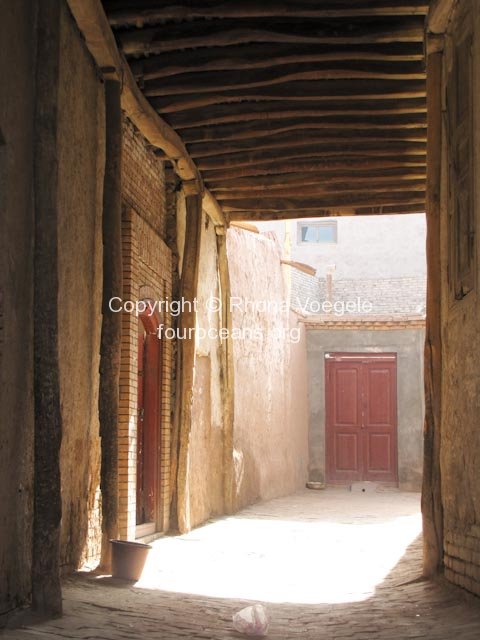

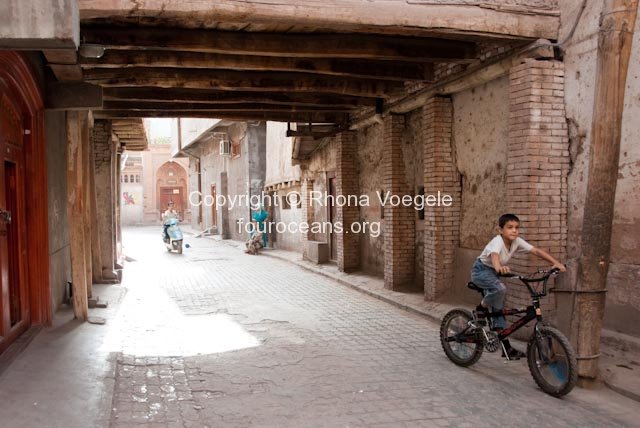

Back in Kashgar I wandered around the old town some more, aware that by the next time I come back (assuming that I probably will) things may be very different. According to people I’ve talked to about 200 people were killed in Kashgar alone during the riots and the overall number of people killed across Xinjiang is more like 2,000 rather than the approximately 200 the government admits to. People I’ve talked to saw mobs of Han Chinese armed with whatever they could find and in search of Uyghurs and when they found their prey the Chinese army was slow/reluctant to do anything about it. It’s an impossible situation, you never know the truth but I know enough not to trust the official government sources. On the train in from Beijing I was asked by the guard if I was a reporter, I’ve never been asked that before in all the travels I’ve done in China. I wonder what would have happened if I’d said yes?

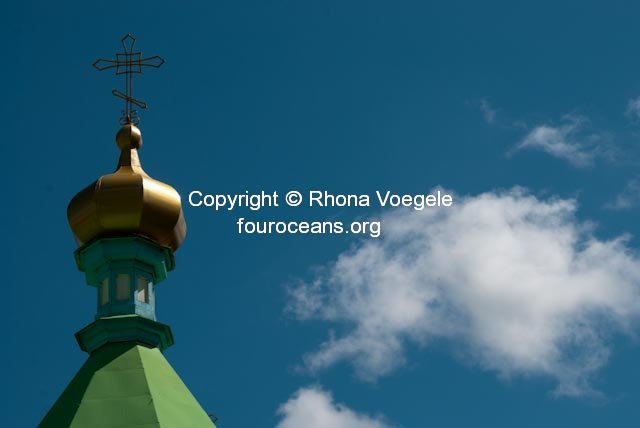

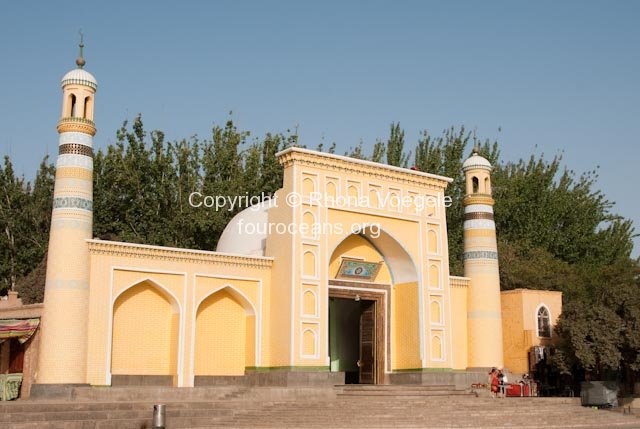

There was a mob of armed soldiers permanently stationed outside the main mosque in Kashgar and on Friday their numbers swelled to about 300. They did drills, brandished machine guns and generally made sure everyone knew who was in charge. Even with this show of “strength” and the 3 more trucks circling the streets (each holding at least 20 more fully armed soldiers) there wasn’t anything like the army presence I saw in Urumqi. There every street corner was like a tableau of Han Chinese weaponry. Of course I have no good photos as the army knows as well as I do that what they’re doing looks more like an occupation than “keeping the peace”. They weren’t keen on having anyone document it.

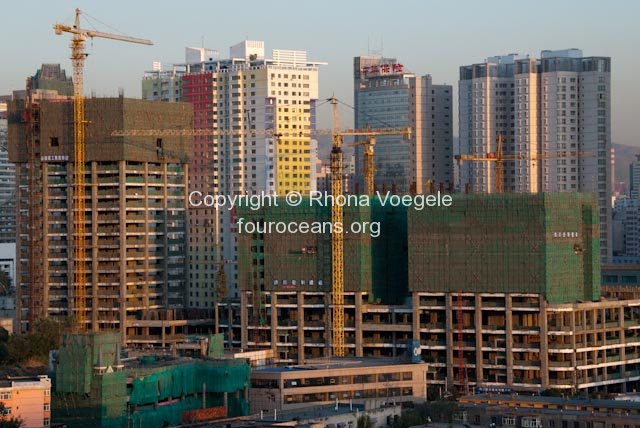

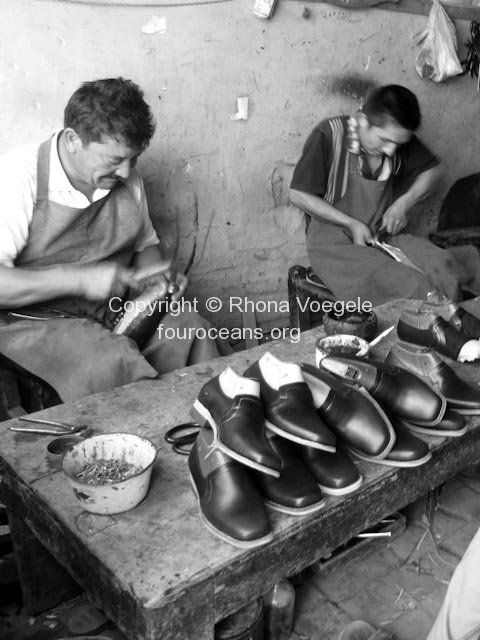

I don’t think anyone has an easy answer to the “troubles” but I think at least part of it stems from the fact that the Uyghurs aren’t being allowed to be a part of the “New China” that’s emerging. They’re discriminated against in the workplace and have more restrictions on them (in their own country) than the newly immigrated Han Chinese. If they could start seeing improvements to their lives, have new opportunities and start feeling the freedoms that come with economic stability, the way the Han Chinese are, then I’d say at least some of them would be happier with the whole situation.

Moving away from politics briefly… Brett joined me on the 28th and we planned on spending the 29th in the hotel room, sleeping, eating and watching movies. Suddenly there was a knock on the door and a staff member told us that the hotel was being closed and everyone had to leave. The police were here. I’m not sure what the official reason given was but the fact that it’s a Uyghur run place opposite the main mosque and the 60th anniversary of the glorious motherland is coming up may have something to do with it. This being China I would say the rat in the wall, the toilet that didn’t flush properly and the broken shower taps weren’t major problems.

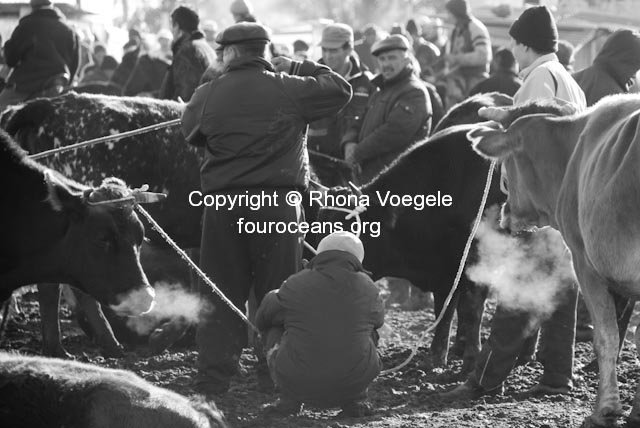

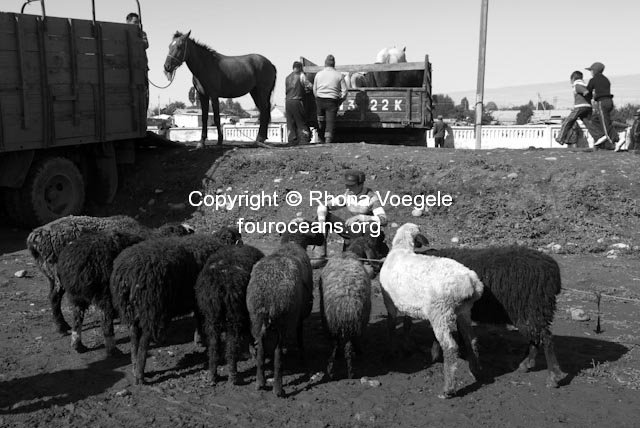

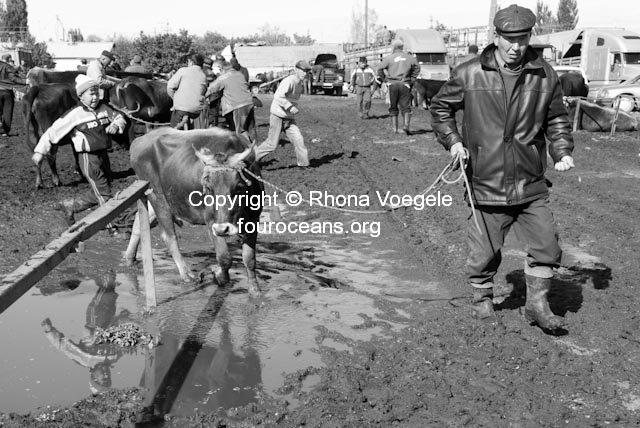

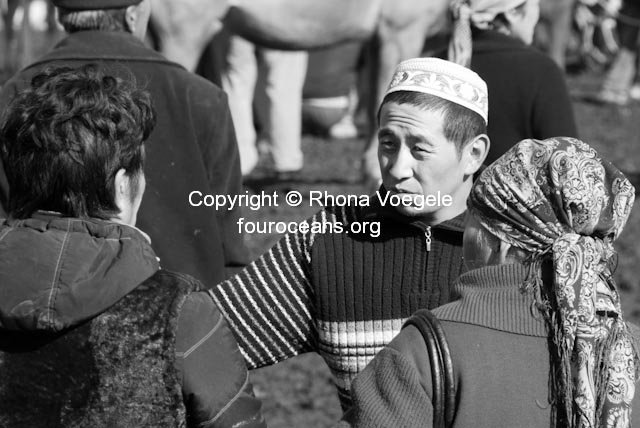

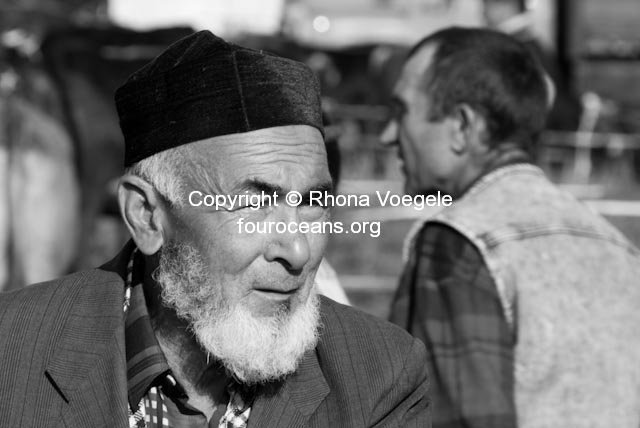

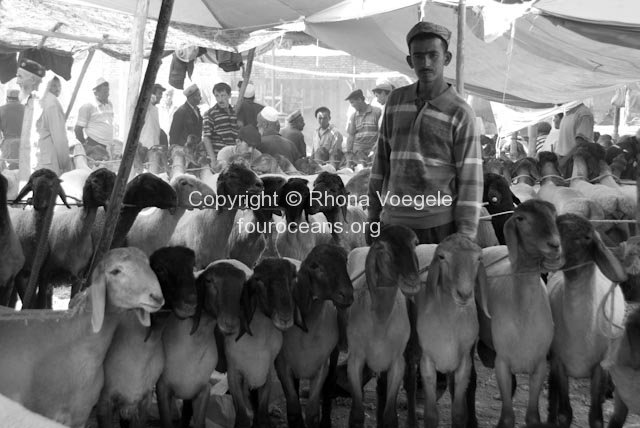

On Sunday we went again to the animal market and the Sunday Market which were dusty and huge accordingly, as they were last time we went. We bought 2 prayer carpets and later I convinced Brett to buy 3 more. For a whopping US$5 per piece it seemed silly not to but maybe that’s just me? A frustrating afternoon at the Bank of China and China Post was how we spent the latter part of our last day before heading to Kyrgyzstan.

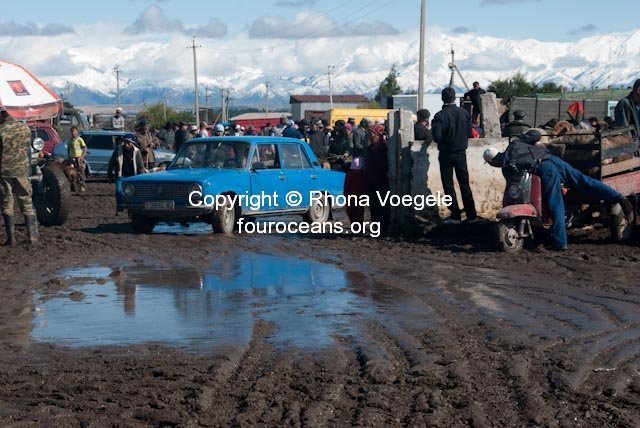

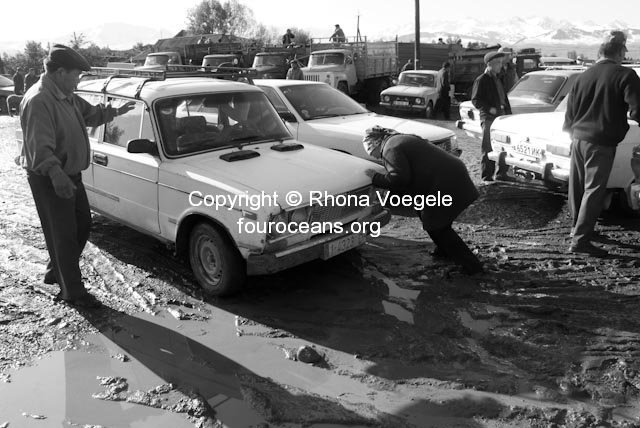

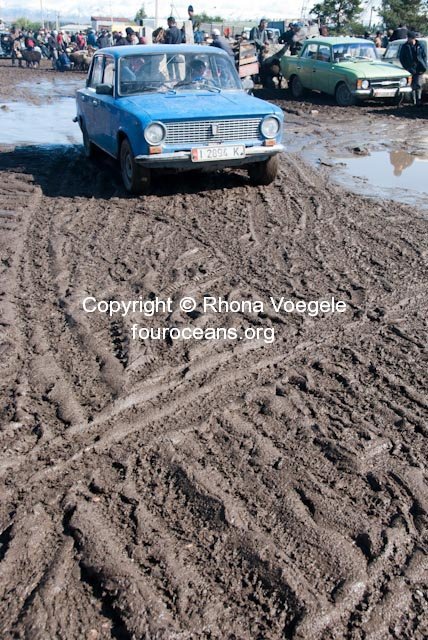

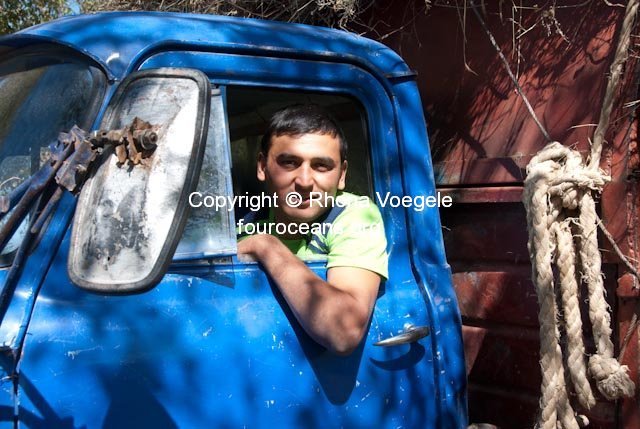

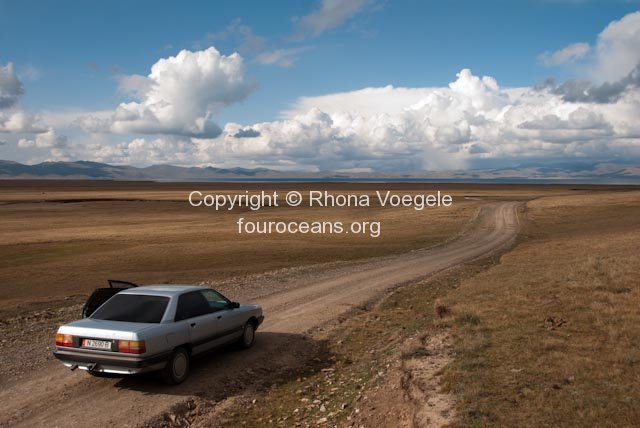

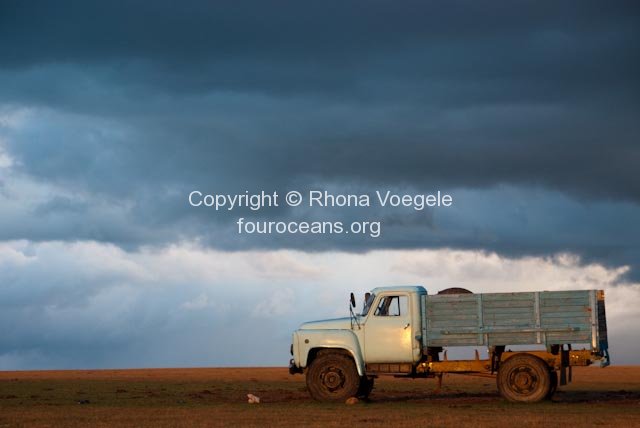

We went via the Torugart Pass into Kyrgyzstan, which is said to be one of the more difficult and temperamental border crossings. This is due to weather, Chinese red tape and all sorts of other random reasons. Our main problem was the abysmal car that we’d been supplied which finally managed to get us to the border 2 hours later than expected. It was only meant to be a 4 hour drive. By the time we limped to the pass there was a hole in the muffler and he had to start in first gear. Once it got going he couldn’t change gear. Admittedly some of the time was probably lost at the Chinese immigration where _every_ _single_ _one_ of our Xinjiang photos had to be checked. Twice. By two different officials. They then let us go without checking our bags at all, though they were very suspicious of our newish passports for some reason?

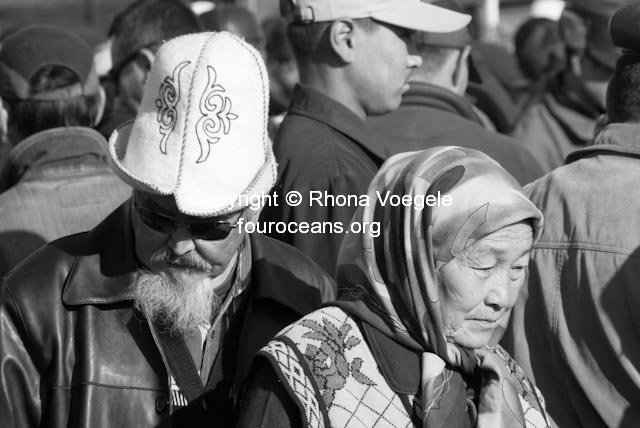

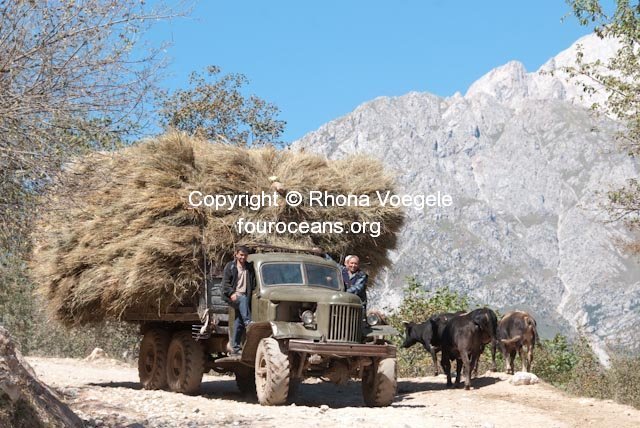

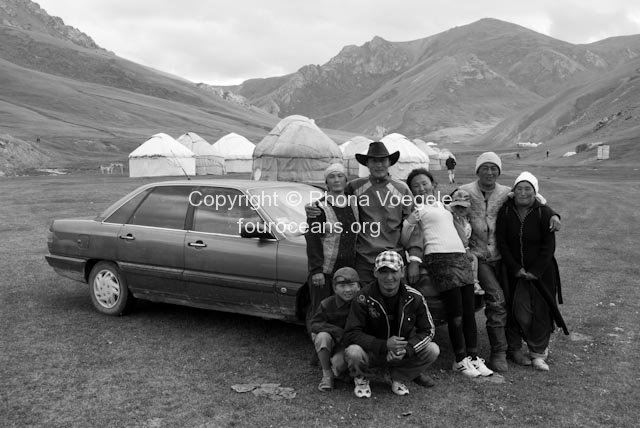

We were welcomed to Kyrgyzstan by a friendly man in a fantastic car. Breathe out… Our first night was spent in a yurt next to the Tash Rabat Caravanserai, an ancient ruin (though nobody knows how ancient) which was apparently a sort of hotel on an old branch of the Silk Road (though nobody is really sure of this either). It was a beautiful little valley and we were really impressed with the way the yurt stay was organised. We woke to a crisp morning and a thin blanket of snow before heading on to Naryn where we took care of some admin and headed out again. Further north in the mountains is a lake called Song Kol which was described as very pretty. It was nice but not amazing, though I may be biased by the world record in toilet trips I made the morning we left. Instead of heading further we stopped in Kochkor where I whined and Brett was sympathetic until my stomach bug passed.

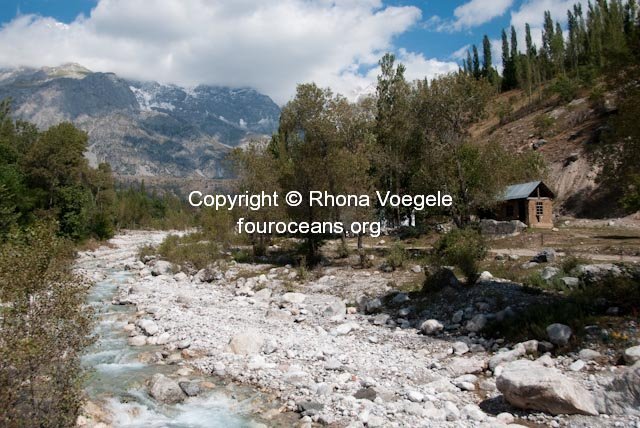

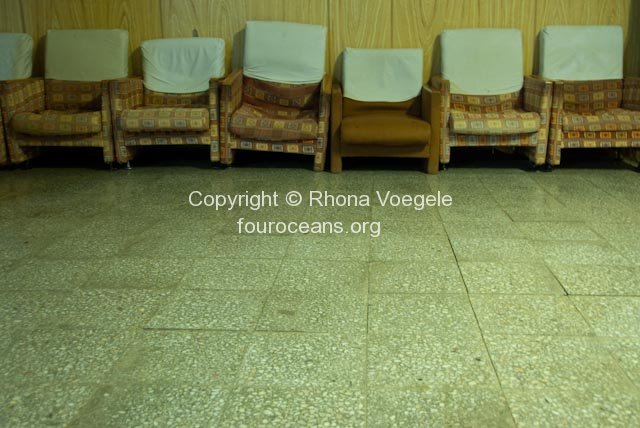

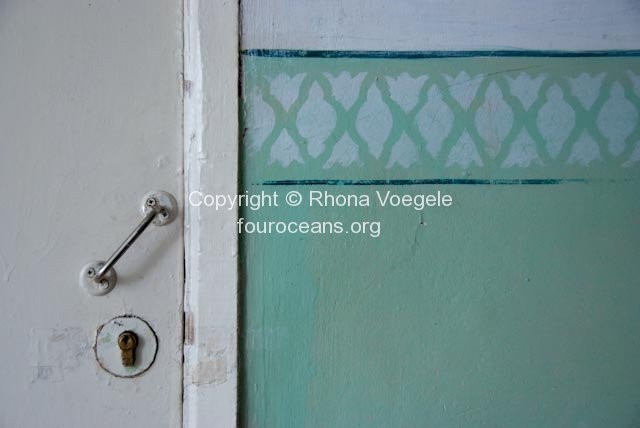

From there we headed to the Karakol area, famous (amongst the few tourists that come here) for its amazing hiking. For the longest leg of the journey we were in a share taxi with a congenial driver and a colony of flies. The 5 of us (yes, that includes the driver) swatted, slapped at and killed as many as possible as we careened along the wet road trying to avoid the many potholes. Best advice for women coming to Kyrgyzstan? Pack a sports bra. Up in one of the valleys near Karakol is the Jeti Oghuz sanatorium, built in 1932 and seemingly unrepaired ever since. There were quite literally chunks of the building missing. The sign on the door of the reception office said that there was lunch break from 1-2pm and at 2:32pm on the dot a lady in a lab coat came back. By around 3:30 we were shown to our room where the toilet cistern was held together with sticky tape (it didn’t work). There was no water in the basin and about a third of the light bulbs worked but when we asked if there was another room we were told that this was the best room available. No wonder the share taxis all stopped to buy cheap vodka. Dinner was surprisingly good, as was breakfast the next day.

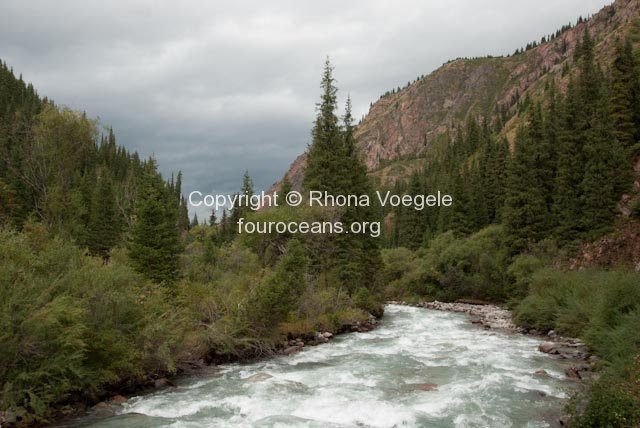

Yesterday we planned on hiking up the valley from the sanatorium but were turned back by rain. So far we’ve been less than impressed with the weather in Kyrgyzstan, though the Lonely Planet lists September as the best time of year to travel here. We’d planned to do more hiking up into some of the (apparently) spectacular mountains but the forecast says more of the same over the next few days so we may just head west and see how we go.